Honorary Doctorate |

|

|||

On May 31, 2007, Terry Mosher received an honorary Doctor of Letters from McGill University. |

||||

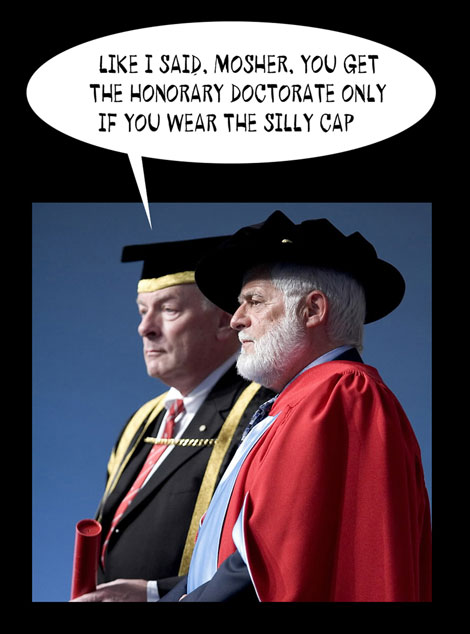

| Dick Pound (left) and Terry Mosher at McGill convocation May 2007 | ||||

The older I get, the more I find myself listening carefully to people who don't say much. And, paraphrasing Voltaire, when it comes to speeches, if you want to be boring, leave nothing out. Therefore, I’ll try to be brief with my remarks here this afternoon. I would like to thank Richard Pound, Heather Monroe-Blum, Robert Rabinovitch and the members of McGill’s Senate for allowing me to be a part of this special moment in time that we are sharing today. This process is not completely unknown to me. My daughters Aislinn and Jessica studied long and hard to become members of McGill’s graduating classes of 1990 and 1992 respectively. I, on the other hand, feel as if I’m sneaking in McGill’s back door here. Suddenly, after one telephone call from Dick Pound, here I am a doctor of letters – and one that doesn’t even spell that well. In fact, with that phone call came a question: What could a high-school dropout possibly have to say to 700 students graduating from Canada’s premier university? As I recently told The McGill Reporter, I was a terrible student as a youngster – an incorrigible rascal in fact, who simply wanted the process of formal education behind me. My teachers agreed – and obliged, by throwing me out of high school on what they indicated was a permanent basis. Finding myself as free as a bird, for the next few years I knocked about, hitchhiking all over North America, spending most of my time sketching whatever I came across in my travels. That resulted in several thousand drawings over a three-year period – and I then surprised myself by deciding to go back to art school to improve my craft. I applied to the École-des-Beaux-Arts in Quebec City, as I had been spending my summers there working as a street artist. The professors said my drawings were good enough that they could start me off in third year. All they needed from me was — my high-school leaving certificate! That happened to be on a Friday. Without so much as blinking, I said I would return on Monday with the diploma. I spent the weekend drawing myself a very fancy graduation certificate – one of the best drawings I’ve ever done, actually. That led to a Bachelor of Arts degree – one I didn’t even have to draw. All in all, I felt pretty lucky. As actor Ben Affleck once told Vanity Fair: "I'm just happy not to be holding up convenience stores." Many of the people I admire have had hardscrabble beginnings. Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple Computers, was also a school dropout. When he delivered the convocation address at Stanford University two years ago, he attributed his phenomenal success to finding out what he loved to do very early in life. I too was fortunate enough to discover early on what it was that I loved to do – I loved to draw. But what should I be drawing? Given my bent for hyperbole and mischief, I thought I might give cartooning a try. Immediately I found my choice to be immensely satisfying, even if, as Molière once said: "It's an odd job, making decent people laugh." Still, when I started out, I knew nothing about my chosen field. I discovered that there wasn’t even a history book on the subject of Canadian political cartooning. So I wrote one, even though it took me ten years to do so. In the process, I got to know every cartoonist working in the country, from Newfoundland to British Columbia – and discovered that collegiality rather than competition with your peers is highly beneficial in the long run. This is not to say that competition is a bad thing. But it is generally best to compete with that person closest to you — yourself. Let me stress then that you will be well served by getting to know as much as you can about every aspect of whatever it is you choose to do. This doesn’t mean, by the way, always playing by the rulebook. Knowing the rules allows you to occasionally take a chance by forgeting them, even though you may sometimes fall flat on your face. The writer and broadcaster Garrison Keillor once urged a group of creative people to have “interesting failures.” I can vouch for that, having had a number of my own face-plants. Satire is, after all, an experimental testing process. We all have faults and weaknesses. Can we admit as much by laughing publicly at our frailties? This trait of being able to laugh at ourselves in public is not a universal one. All societies, of course, have a strong tradition of humour. But is it humour at the expense of our perceived enemies – in other words, propaganda ¬– or is it genuine satire that pokes fun at our own? These cultural differences came to the fore in the recent uproar over the Danish cartoons of Mohammed. Many Muslims were genuinely angered. Danish products were boycotted, embassies burned, churches destroyed and hundreds died in different Muslim countries. But as a Globe and Mail editorial stated: “The best cartoons hurt. In democracies worthy of the name, authorities grit their teeth and leave the cartoonists alone. It would be tragic if the controversy over the Danish cartoons placed a chill on this most necessary of art forms.” And this from The Economist: “Freedom of expression is a pillar of western democracy, as sacred in its own way as Mohammed is to pious Muslims.” This is an issue that isn’t going away any time soon. One of the positive aspects of the Internet is that it has made it easier for each of us to publish our views. But it has also made it easier for groups to mobilize attacks on those whose views they do not like. I hope that all of you, the first Internet generation, will stand in defense of freedom of expression whenever it is threatened. Allow me one final point. Even though I work in journalism, often a cynical business, I do trust in the expertise of my colleagues, my editors and even the production wizards who magically get my cartoon onto the editorial page of The Gazette each and every day. But how often do we acknowledge the competence and caring of certain people in our lives – partners, family, friends and workmates? For, no matter how good you think you are at what you do, you’ll need the talents of those around you to help you along the way. Let me close with a favorite anecdote illustrating just that. Back in the 1970s, the boxer Muhammed Ali was the most famous person on earth. One day, Ali got on an airplane. The flight attendant politely asked him to do up his seat belt. Ali replied arrogantly. “Superman don’t need no seat belt!” The attendant shot back, “Superman don’t need no airplane either!” Congratulations to you all. Have interesting lives. And now, please go out and change the world. |

||||